This article sets about explaining Project Mainline, one of several Google initiatives to modularize Android to make it more updatable. The original goal behind Project Mainline was to improve the speed at which Android users receive security patches for critical system components, but it is also now used to roll out new Android features to users running different Android versions without needing them to apply a full OS update.

Although Project Mainline was introduced several years ago, it has expanded to encompass more and more parts of Android over time. With the recent release of Android 13 to AOSP, this article was written with the Android 13 changes to Project Mainline in mind. However, for a full list of Project Mainline updates specific to the Android 13 release, refer to Mishaal's coverage. And for an even deeper exploration into the internals of Android beyond Project Mainline, scroll to the end to learn more from the resources I've prepared.

The motivation for Project Mainline

In the years since its inception, Android has grown to encompass most of the mobile landscape and become the de facto operating system, the "Windows" of the mobile world. iOS maintains its considerable market share, yet it is intentionally limited to Apple's own devices. This leaves Android as the platform of (no) choice for all other vendors, thanks to Android's open source nature (AOSP) and free license, which allows a fairly large breadth of vendor customization.

The vast adoption of Android, however, is not without drawbacks. Though all vendors fork the same AOSP source tree, each is incentivized to add more and more proprietary customizations — whether in order to support specific hardware configurations or to differentiate by means of some novel UI or system application. Though discouraged from doing so, many vendors modify the contents of the system partition or change AOSP sources directly. Thus arose one of Android's most prominent problems — fragmentation.

Fragmentation occurs when AOSP customizations are significant enough to make a generic AOSP build incompatible with a device "as is". This means that it falls on the device manufacturer to keep AOSP up to date — no mere feat given Android's steady, annual progression. Users suffer from this first hand, as their devices become obsolete as early as 18 months after they were brand new. Modders experience the tribulations of creating a custom AOSP build for their device, only to realize some hardware component suddenly stops working. The ecosystem as a whole suffers as the majority of devices get their updates infrequently and often far too late (if at all), exacerbating security flaws and inhibiting the adoption of the most up-to-date Android experience.

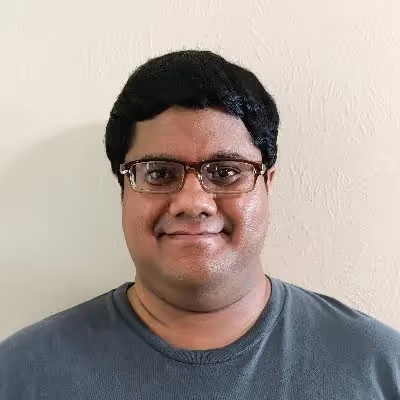

Google first set out to address this problem in Android 8.0 Oreo with "Project Treble". This primarily involved a complete rearchitecture of Android's Hardware Abstraction Layer (the components used to interface the generic AOSP code with vendor/BSP-specific hardware aspects). A more pertinent change was in enforcing a clear-cut "division of responsibilities" through what was to become the standard partitioning layout of all devices:

- /system — the system partition would now be exclusively comprised of AOSP code and thus become the responsibility of Google alone.

- /vendor — would be used for the BSP (Board Support Package) binaries and files. These include the hardware-specific components needed to interface with the SoC components, ie. the baseband, sensors, camera, etc. Despite the numerous device brands, there are only a few silicon vendors, such as Qualcomm, Samsung (Exynos), MediaTek, and UNISOC (formerly Spreadtrum)).

- /odm — would be used for files from the "Original Device Manufacturer", that is, the software vendor and brand of the device (e.g. Xiaomi, Samsung, OPPO, etc).

- /product — would be used for device-specific idiosyncrasies like, for example, the minor differences between a Pixel 6 and 6a.

The partitions' filesystems are also similarly laid out (see the figure below), so as to effectively form a "search path" in reverse order of specificity. This way, the AOSP code first seeks out the product-specific files, if any, followed by those of the brand, then those of the SoC, and — if none are found or required — defaults to its own files, which are generic enough to serve all devices*.

Thus, in a perfect world (effectively, from Android 9 and later), all Android devices — regardless of vendor — would use identical /system partitions. These could, in effect, be maintained solely by Google. Google could further push AOSP images as they see fit, relieving the vendor of the need and burden of doing so. Devices could more easily be kept up to date, and advanced use cases (notably, Generic System Images), could be considered as well.

How Project Mainline works

Android 10 brought the promise of "Project Mainline". Although it was initially conceived for out-of-band security updates, it's also enabling new feature and API backports. The big idea behind Project Mainline is to modularize system components, so that — while still part of AOSP — they can be updated in a manner not unlike a standard APK update on Google Play.

These Project Mainline modules, also called modular system components, are distributed in either the standard APK format or the Android Pony Express (APEX) format introduced in Android 10. Which format is used largely depends on how early in the boot process the component needs to be initialized, as APEX modules can be used much earlier in the boot process than APK-based modules can. The APK format is also less flexible when it comes to system modules, as it is primarily designed for Android apps. APEX files can contain native shared libraries, native executables, JAR files, data files, config files, and yes, even APKs. A more detailed explanation of the APEX format can be found in a following section.

Every Project Mainline module

Android 10 launched with thirteen Project Mainline modules. That number has more than doubled as of Android 13, or tripled if you consider undocumented modules. However, not every Mainline module will be present on any given device running a particular Android version. This is because Android Partners are only required to preload the modules listed in GMS Requirements, a document outlining the requirements that software builds must meet in order to receive Google's blessing to integrate GMS. Google requires Android Partners to preload most modules listed in table 1 below on Android 13 handheld devices, with the exception of the Bluetooth, UWB, and Wi-Fi modules.

Google provides its Android Partners a precompiled, presigned APK or APEX file for each module they require to be integrated. This is so Google can push updates to these modules through Google Play. Google-built modules typically have package names beginning with com.google instead of com.android, but the tables below will list the package names for the modules from AOSP for consistency.

Given the sheer number of Project Mainline modules, this section will not explain in detail the purpose of every module. Instead, we encourage you to visit the AOSP documentation for Project Mainline to learn about each individual module. The table below lists each module, its package name, its format (APK or APEX), when it was introduced, and what feature(s) it implements.

Table 1: Android’s Project Mainline modules (Source: Android Internals, Volume II, Chapter I)

The above table only lists those modules that have been documented officially by Google. Google only documents modules as part of Project Mainline when they become updatable — certain modules like ART were originally packaged as non-updateable APEX files. Several modules are not documented on the aforementioned source.android.com page as they are not updatable and thus not considered part of "Project Mainline". However, we are listing them below for completeness:

Table 2: Android's undocumented modules (Credits: Mishaal Rahman)

Lastly, devices may ship vendor-specific modules. The camera HAL on Google Pixel devices, for example, is packaged in the com.google.pixel.camera.hal APEX file located in /vendor/apex. Seeing as vendor APEXes are not part of AOSP, these will not be documented in this article.

What features have Project Mainline module updates brought?

The further modularization of Android has already born fruit several times since its inception. Through Mainline updates, Google has brought (or will bring) the following features to existing devices without the need for an OS update:

- mDNS .local resolution: The November 2021 Google Play System Update allowed the DNS Resolver module to recognize the .local domain (RFC6762) with Multicast DNS, in the implementation of getaddrinfo().

- Photo Picker: Officially introduced as one of the new features of Android 13, the Photo Picker was backported to Android 11-12L devices with the May 2022 Google Play System Update.

- DNS over HTTP/3 support: An update to the DNS Resolver module in the July 2022 Google Play System Update adds support for using DNS-over-HTTP/3 (DoH3) as the encrypted DNS protocol for the "private DNS" feature on all devices running Android 11-13 and some devices running Android 10.

- New garbage collection algorithm based on userfaultfd: Through an upcoming update to the ART module, Google will introduce a new garbage collection algorithm based on Linux's userfaultfd feature that reduces memory overhead.

- Safety Center: The new unified security & privacy settings page in Android 13 is part of the PermissionController app, which is contained within the Permission module. This, along with the new "Protected by Android" branding, will be enabled in an upcoming Google Play System Update.

These are only some of the more notable features introduced through Project Mainline module updates. Google does not provide a detailed changelog of every feature and changed introduced in monthly Google Play System Updates (GPSU), though they do document some changes in their "what's new in Google System Updates" support page. This page mainly lists changes introduced through updates to the Google Play Store and Google Play Services applications, but it also lists changes introduced through Google Play System Updates.

The structure of APEX packages

APEX packages are a special case of APKs — that is, ZIP/JAR files signed by apksigner. AOSP's /system partition now has a /system/apex directory, in which the default modules are provided. Additional modules that are not compiled by default when building AOSP but can optionally be added to builds are placed in /system_ext/apex. Vendor APEXes are installed by the build system in the /vendor/apex directory.

When the device first boots, these are mounted and used. As new APEX modules become available, they are downloaded into /data/apex. A quick version check can then be made to determine which version is the most up to date.

redfin:/system/apex $ ls -l

total 184784

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 336254 2008-12-31 19:00 com.android.apex.cts.shim.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 7696384 2008-12-31 19:00 com.android.cronet.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 38125568 2008-12-31 19:00 com.android.i18n.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 8249344 2008-12-31 19:00 com.android.runtime.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 48242688 2008-12-31 19:00 com.android.vndk.current.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 3318377 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.adbd.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 442368 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.adservices.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1286760 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.appsearch.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 22458987 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.art.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 9728620 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.bluetooth.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 4829801 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.cellbroadcast.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 2384564 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.conscrypt.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 2855528 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.extservices.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 356966 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.ipsec.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 2634419 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.media.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 8561328 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.media.swcodec.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 3723880 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.mediaprovider.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 3703399 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.neuralnetworks.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 119401 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.ondevicepersonalization.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 852586 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.os.statsd.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 5710442 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.permission.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1835694 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.resolv.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 98922 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.scheduling.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 344680 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.sdkext.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 331776 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.telephony.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 4039274 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.tethering.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 950272 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.tzdata4.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1176171 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.uwb.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 3527272 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.android.wifi.apex

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1794048 2008-12-31 19:00 com.google.mainline.primary.libs.apex

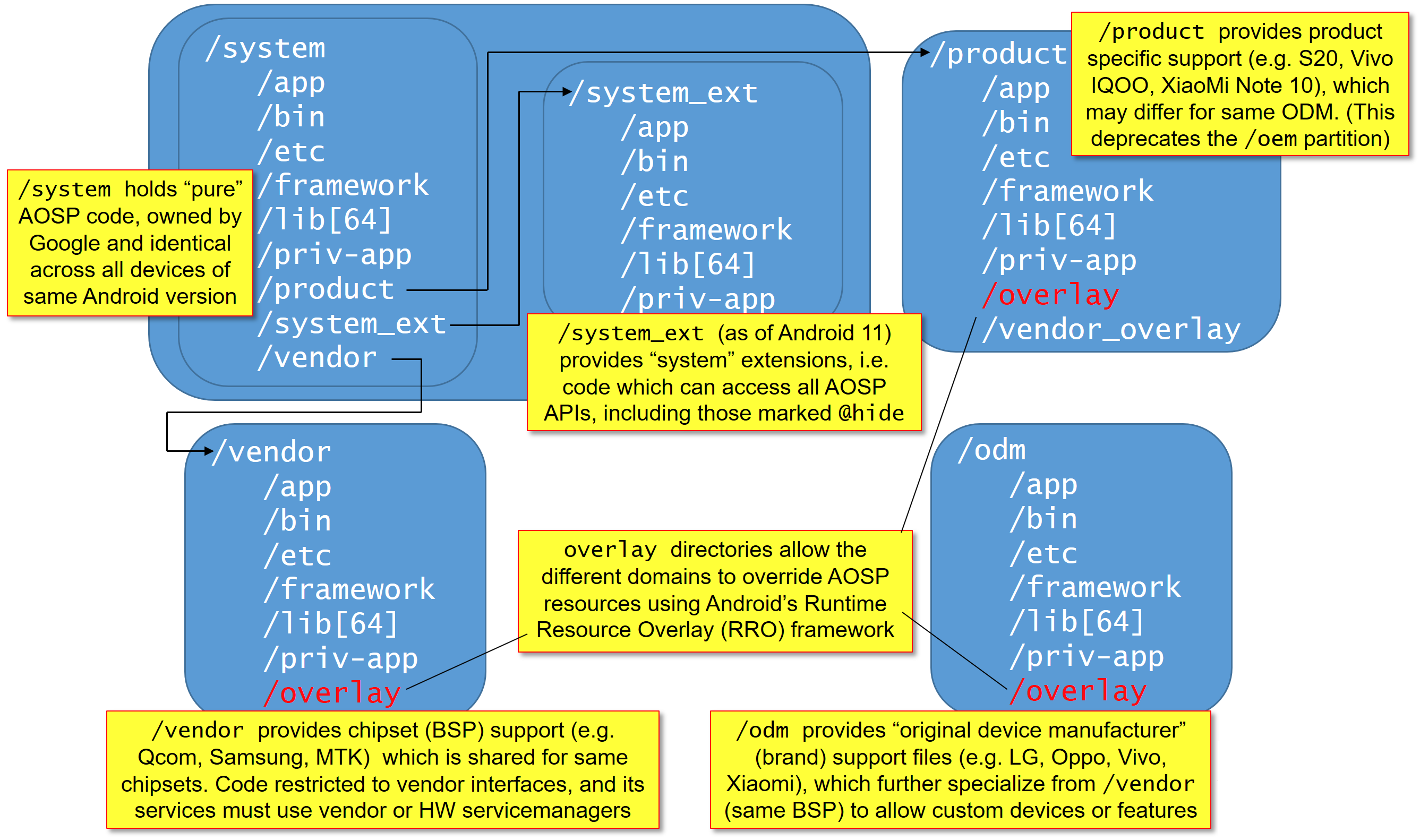

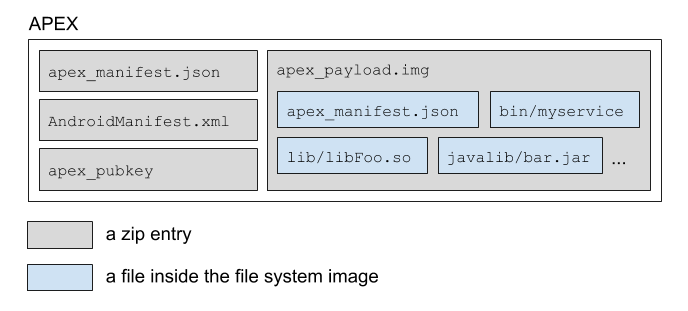

The layout of APEX files is given by the official AOSP documentation as follows:

A more detailed view is provided in the following illustration, which focuses on the APEX Manifest — traditionally, in XML form, but recently (as of around Android 11) in Google's favorite protobuf format:

But let's examine a real APEX file hands-on. Since there are plenty of APEXes in /system/apex, we connect to the device and adb pull one of them, Cronet, as an example:

morpheus@Forge /tmp $ adb pull /system/apex/com.android.cronet.apex

/system/apex/com.android.cronet.apex: 1 file pulled, 0 skipped. 31.0 MB/s (7696384 bytes in 0.236s)

morpheus@Forge /tmp $ file com.android.cronet.apex

com.android.cronet.apex: Java archive data (JAR)

morpheus@Forge /tmp $ unzip -l !$

unzip -l com.android.cronet.apex

Archive: com.android.cronet.apex

Length Date Time Name

--------- ---------- ----- ----

7573504 01-01-2009 00:00 apex_payload.img

1032 01-01-2009 00:00 apex_pubkey

72486 01-01-2009 00:00 assets/NOTICE.html.gz

40 01-01-2009 00:00 resources.arsc

1112 01-01-2009 00:00 AndroidManifest.xml

1527 01-01-2009 00:00 apex_build_info.pb

102 01-01-2009 00:00 apex_manifest.pb

32 01-01-2009 00:00 stamp-cert-sha256

868 01-01-2009 00:00 META-INF/CERT.SF

2244 01-01-2009 00:00 META-INF/CERT.RSA

733 01-01-2009 00:00 META-INF/MANIFEST.MF

--------- -------

7653680 11 files

Every APK is a JAR, and every JAR is a ZIP. From ZIP we get the file format, archiving, and compression/storage methods. From JAR we get the META-INF/ directory, which contains the traditional signature of jarsigner (but not of apksigner, which uses special ZIP blocks). From APK we get the AndroidManifest.xml:

morpheus@Forge /tmp $ aapt d xmltree com.android.cronet.apex AndroidManifest.xml

N: android=http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android

E: manifest (line=17)

A: android:versionCode(0x0101021b)=(type 0x10)0x1

A: android:compileSdkVersion(0x01010572)=(type 0x10)0x21

A: android:compileSdkVersionCodename(0x01010573)="Tiramisu" (Raw: "Tiramisu")

A: package="com.google.android.cronet" (Raw: "com.google.android.cronet")

A: platformBuildVersionCode=(type 0x10)0x21

A: platformBuildVersionName="Tiramisu" (Raw: "Tiramisu")

E: application (line=20)

A: android:hasCode(0x0101000c)=(type 0x12)0x0

E: uses-sdk (line=21)

A: android:minSdkVersion(0x0101020c)=(type 0x10)0x1d

A: android:targetSdkVersion(0x01010270)=(type 0x10)0x21

As the above shows, the Manifest describes an APK with a target SDK of 33 (0x21). As a codeless APK (hasCode: 0), there isn't much more to describe in the manifest — so the APEX metadata is in a separate file, apex_manifest.pb:

morpheus@Forge tmp$ unzip com.android.cronet.apex apex_manifest.pb

Archive: com.android.cronet.apex

inflating: apex_manifest.pb

morpheus@Forge tmp$ hexdump -C apex_manifest.pb

00000000 0a 12 63 6f 6d 2e 61 6e 64 72 6f 69 64 2e 63 72 |..com.android.cr|

00000010 6f 6e 65 74 10 01 42 0d 6c 69 62 61 6e 64 72 6f |onet..B.libandro|

00000020 69 64 2e 73 6f 42 07 6c 69 62 63 2e 73 6f 42 08 |id.soB.libc.soB.|

00000030 6c 69 62 64 6c 2e 73 6f 42 09 6c 69 62 6c 6f 67 |libdl.soB.liblog|

00000040 2e 73 6f 42 07 6c 69 62 6d 2e 73 6f 4a 18 6c 69 |.soB.libm.soJ.li|

00000050 62 63 72 6f 6e 65 74 2e 38 30 2e 30 2e 33 39 38 |bcronet.80.0.398|

00000060 36 2e 30 2e 73 6f |6.0.so|

The .pb extension denotes the ProtoBuf format, a serialization method Google is especially fond of and has become a standard in ChromeOS and Android. With a little help from the AOSP sources, we see that element "0xa" is ;requireSharedApexLibs and that the APEX supplies libronet.80.0.3986.0.so.

The meat of the APEX is in apex_payload.img. This is a raw filesystem image signed by apex_pubkey. APEX image payloads are currently formatted in EXT4, but for Android 13 launch devices with kernel version 5.10 or higher, Google is shifting to formatting them with EROFS for additional storage savings. Knowing this, we can extract and try to mount it, in the same way Android's apexd does:

morpheus@Forge tmp$ unzip com.android.cronet.apex apex_payload.img

Archive: com.android.cronet.apex

extracting: apex_payload.img

[morpheus@Forge tmp]$ file apex_payload.img

apex_payload.img: Linux rev 1.0 ext2 filesystem data, UUID=7d1522e1-9dfa-5edb-a43e-98e3a4d20250 (extents) (large files) (huge files)

#

# Following requires root, since mounting with options:

#

root@Forge /tmp # mkdir /mnt1

root@Forge /tmp # mount -o loop $PWD/apex_payload.img /mnt1

mount: /mnt1: wrong fs type, bad option, bad superblock on /dev/loop0, missing codepage or helper program, or other error.

#

# Errors reported! Try dmesg:

#

root@Forge /tmp # dmesg | tail

...

[286740.820105] loop: module loaded

[286740.857796] EXT4-fs (loop0): couldn't mount RDWR because of unsupported optional features (4000)

[286740.913600] blk_update_request: I/O error, dev loop0, sector 0 op 0x1:(WRITE) flags 0x800 phys_seg 0 prio class 0

[286740.913937] blk_update_request: I/O error, dev loop0, sector 0 op 0x1:(WRITE) flags 0x800 phys_seg 0 prio class 0

#

# ext4 has the notion of "optional features", which may be ignored if mounting read-only

#

root@Forge /tmp # mount -o ro,loop $PWD/apex_payload.img /mnt1

root@Forge /tmp # cd /mnt1

root@Forge /mnt1 # ls -RF

.:

apex_manifest.pb etc/ javalib/ lib/ lib64/ lost+found/

./etc:

permissions

./etc/permissions:

org.chromium.net.cronet.xml

./javalib:

org.chromium.net.cronet.jar

./lib:

libcronet.80.0.3986.0.so

./lib64:

libcronet.80.0.3986.0.so

./lost+found: # An artifact of mkfs, for fsck use (thus empty)

(Android 12 introduced the ability to compress pre-installed APEX files stored on read-only partitions. This will not be addressed here, but it is worth mentioning.)

The manual mounting of an APEX payload demonstrated here is performed automatically by Android's apexd. (Mounting an APEX payload requires the Linux kernel's loop driver included in Linux 4.9+.) As an automatic service, apexd starts up from its own .rc file:

service apexd /system/bin/apexd

interface aidl apexservice

class core

user root

group system

oneshot

disabled # does not start with the core class

reboot_on_failure reboot,apexd-failed

service apexd-bootstrap /system/bin/apexd --bootstrap

user root

group system

oneshot

disabled

reboot_on_failure reboot,bootloader,bootstrap-apexd-failed

service apexd-snapshotde /system/bin/apexd --snapshotde

user root

group system

oneshot

disabled

As the above shows, apexd is started under no less than three possible configurations. The first one is the apexd-bootstrap. This is a disabled service, so it is started from AOSP's init.rc explicitly:

on early-init

# Run apexd-bootstrap so that APEXes that provide critical libraries

# become available. Note that this is executed as exec_start to ensure that

# the libraries are available to the processes started after this statement.

exec_start apexd-bootstrap

# Generate linker config based on apex mounted in bootstrap namespace

update_linker_config

on property:apexd.status=ready && property:ro.product.cpu.abilist32=*

exec_start boringssl_self_test_apex32

on property:apexd.status=ready && property:ro.product.cpu.abilist64=*

exec_start boringssl_self_test_apex64

service boringssl_self_test_apex32 /apex/com.android.conscrypt/bin/boringssl_self_test32

service boringssl_self_test_apex64 /apex/com.android.conscrypt/bin/boringssl_self_test64

In the bootstrap configuration, apexd iterates over /system/apex packages and performs the mounts. After apexd-bootstrapis started, the update_linker_config directive — an /init built-in — is used to modify Bionic's linker (through /linkerconfig) so as to point to any APEX packages that were mounted as a result. Apexd communicates its status through the apexd.status system property. When it is ready, BoringSSL — a critical component of the system (as an SSL/TLS stack) is self tested from its (by now, mounted) package.

The initialization continues:

on post-fs-data

mkdir /metadata/apex 0700 root system

mkdir /metadata/apex/sessions 0700 root system

# On some devices we see a weird behaviour in which /metadata/apex doesn't

# have a correct label. To workaround this bug, explicitly call restorecon

# on /metadata/apex. For most of the boot sequences /metadata/apex will

# already have a correct selinux label, meaning that this call will be a

# no-op.

restorecon_recursive /metadata/apex

# Make sure that apexd is started in the default namespace

# and start apexd

# before starting apexd.

# /data/apex is now available. Start apexd to scan and activate APEXes.

# that apexd is started cleanly here (set apexd.status="") and that it is

mkdir /data/apex 0755 root system encryption=None

mkdir /data/apex/active 0755 root system

mkdir /data/apex/backup 0700 root system

mkdir /data/apex/decompressed 0755 root system encryption=Require

mkdir /data/apex/hashtree 0700 root system

mkdir /data/apex/sessions 0700 root system

mkdir /data/apex/ota_reserved 0700 root system encryption=Require

setprop apexd.status ""

restart apexd

mkdir /data/misc/apexdata 0711 root root

mkdir /data/misc/apexrollback 0700 root root

# Wait for apexd to finish activating APEXes before starting more processes.

wait_for_prop apexd.status activated

perform_apex_config

# Allow apexd to snapshot and restore device encrypted apex data in the case

# completed and apexd.status becomes "ready".

exec_start apexd-snapshotde

exec - system system -- /system/bin/tzdatacheck /apex/com.android.tzdata/etc/tz /data/misc/zoneinfo

In the above, we see that /data/apex directories — where downloadable APEX packages and their metadata are stored — is created (since /data may be empty after a factory reset). The apexd daemon is started again, and when it signals its status is "activated", perform_apex_config, another /init built-in (from Android 11) reconfigures the linker configuration, if necessary.

Updating Project Mainline modules

Written by Mishaal Rahman

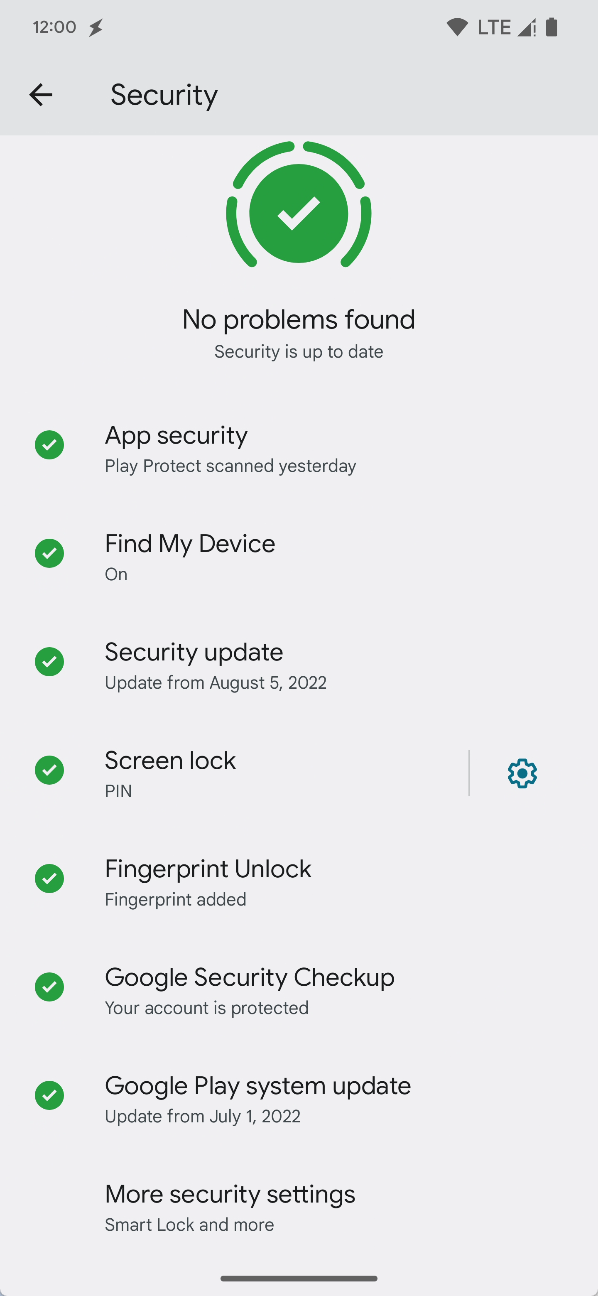

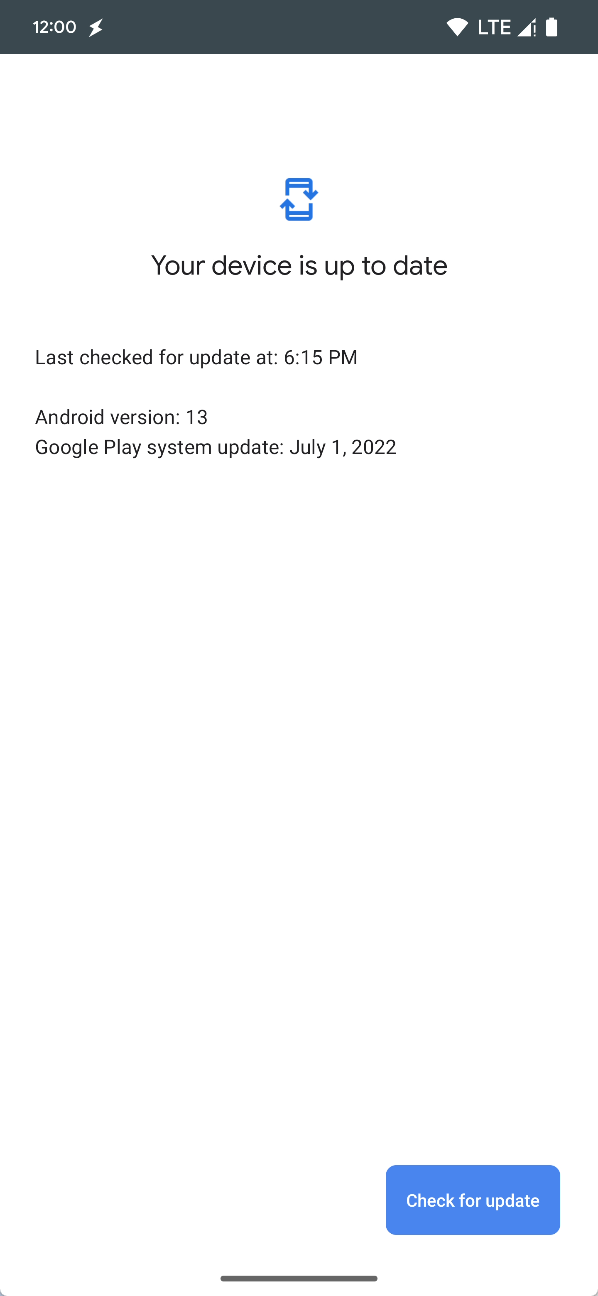

APEX packages can be manually installed through Android's package installer like standard APKs, though this requires the use of the pm install --apex command. Doing so is difficult on GMS Android devices as Google-signed APEX packages are not readily obtainable without root access, and there is no online repository of module updates. Instead, GMS Android users should navigate to Settings > Security > Google Play system update, which launches the Mainline module updater activity in Google Play, to check for and download new Mainline updates.

Once a Google Play System Update has been installed, the system may reboot to install staged APEX or APK files. Devices running Android 11 and above may support soft restarts, ie. user space reboots, enabling the restarting of userspace components while keeping Credential Encrypted (CE) storage unlocked. Server-based resume-on-reboot on Android 12+ goes a step further by using reboot readiness to time this restart when the device is idle, while keeping the data used to unlock CE safe and secure. If either is implemented, this enables Mainline updates to be installed without prompting the user.

Google releases Mainline module updates as part of a "train", ie. a bundle of modules that are downloaded and installed at the same time. This is in contrast to Android app updates which are rolled out individually. When a module train rolls out, the version number of the ModuleMetadata app is incremented, which is where Settings derives the Google Play System Update version.

In case of a botched module update, Android's RollbackManager can roll the update and its data back to the previous version installed on the device. Rollbacks are automatically triggered when there are 5 ANRs or process crashes within 1 minute after an update or if any native service crashes repeatedly. If there's no network connectivity, a rollback will also be triggered for the network stack.

The command-line provides some useful tools for managing APEX module installations. The pm list packages --apex-only --show-versioncode command can be used to list all installed APEX packages and their versions. Meanwhile, the new transparency manager CLI introduced in Android 13 allows for independently comparing the cryptographic signature of each module against Google's transparency log.

Summary

This article gave a detailed account of Project Mainline modules and their behind-the-scenes operation. APEX is an important addition to Android's features (as of Android 10), since it allows a modular architecture, which provides for easy updates, bringing new features, bug fixes or security patches — all without the need for an OS update. As Android progresses, more and more components are modularized and packaged by APEX.

The article was written by Jonathan Levin with the invaluable insights provided by Mishaal Rahman. If you liked this content, consider taking a look at the books Android Internals::Power User's View and Android Internals::Developer's View. The two books provide unprecedented detail into the inner workings of Android — from the Linux system/adb shell perspective (Volume I), and from the framework implementation and infrastructure (Binder, Dalvik/ART, etc.) perspectives (Volume II). The books go above and beyond Google's documentation, elucidating Android's most undocumented domains, and detailing its operational aspects, aiming to cover every single daemon, service, and AOSP files of significance. Planned soon are Volume III (Security) and IV (Advanced topics, including hardware, graphics, media, baseband, networking, and more). For more information and free command line tools, please visit newandroidbook.com!

* It's worth mentioning that all the partitions and APEX packages are digitally signed (using DM-Verity) and backed by Android Verified Boot, so as to make them unmodifiable on non-rooted devices — much to the chagrin of modders